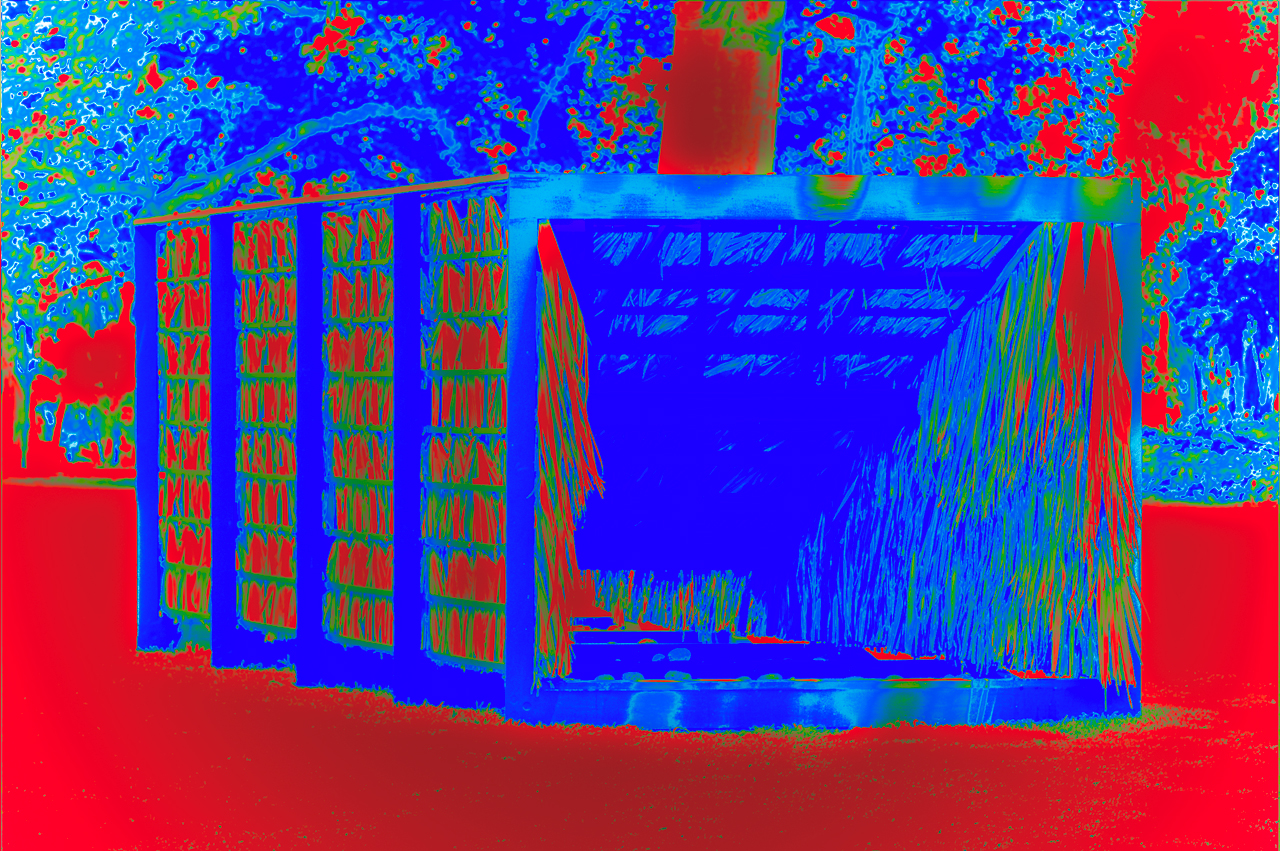

Thatch Assembly with Rocks

Sculpture

Foster Botanical Garden, Honolulu Biennial

O'ahu, Hawai'i

March 8, 2017 - May 8, 2017

Curators: Fumio Nanjo, Ngahiraka Mason

Material: wood, palm, rock

Dimensions: 10'-0" W x 16'-0" L x 8’-8” H

This anachronistic study invites discourse on the role of island-based materials in the future recovery of ahupua‘a.

Sean Connelly’s installation at Foster Botanical Garden offers an intervention in time where traditional thatching materials local to Hawai‘i remain a primary building technology for architectural and aesthetic achievement leading up to the enactment of Hawaiʻi’s Statehood in 1959. In so doing, Connelly counters the normalization of industrial steel as a primary means of structural or sculptural pursuit. His use of natural material references its traditional use as a structural feature of Pacific architecture, favoring a localized form of construction that provokes historical and cultural dialogues. Drawing upon his architectural background, he offers room for rumination on island-based materials and continuity of the ahupuaʻa – the multifaceted, highly sustainable system of land division and management traditional to Native Hawaiians.

PROJECT ANNOTATIONS

Time travel is the first in the set of strategies that comprise Thatch Assembly with Rocks (2060s), a sculptural material study that explores architecture as economy of islands; as an assembly of material and time into systems as significant and necessary as shelter and information. The outdoor siting of this project creates a moment to consider how islands are bound to the scale of building. As buildings are founding components of local and global economic systems, they represent the physical storage of assets (and liabilities) produced across the array of livelihoods experienced on Earth. In the links between shelter and economy, the pursuit of island-based materials in Hawai‘i architecture is critical to the recovery of ahupua‘a, a fundamental technic of economy.

Thatch Assembly with Rocks (2060s) concerns the history of architecture in Hawai‘i, in the decades surrounding Statehood (1959). The installation offers an intervention in time where traditional thatching materials local to Hawai‘i remain a primary building technology for architectural and aesthetic achievement. Surrounding this time, achievements in American architecture underpinning the avant-garde of twentieth century technology accompanied advancements in national and global steel markets emerging from the second world war. Among the most prominent steel works in architecture, Mies Van Der Rohe’s Crown Hall (1956) is credited as the world’s first realization of a clear-span structure to produce universal space—a general space freed in the absence of interior structural columns made habitable through a mechanically conveyed atmosphere enclosed in glass completely. Crown Hall represents a primary emergence from a history of thermal systems in architecture: passive (non-mechanical) buildings habitable within a thickness of opaque walls, columns, and corridors shielding the interior from climate. These tectonic advancements of steel and glass in modern architecture are relative to the history of their application in continental climates. The declaration of space as never before having being universal leads to a moment of speculation regarding the tropics. The thatched Polynesian canoe house with a clear-span timber structure is an oceanic analogue of modern architecture’s universal gem. Thatching—the primary universal building technique extending from ancient times worldwide—requires the use of material that is readily available, durable (lifecycle 15-20 years), with installation processes that are iterative and replicable. Yet, despite the prerogative of modern architecture to address site critically wherever it goes (see Gropius House, 1938), as steel building prevails internationally and in places as remote and tropical as Hawai‘i, regional [link: Kenneth Frampton] building resources like palm fronds for thatching are largely absent from its then vanguard repertoire of epistemology, material, and technique. In the proliferating spans of glass and steel dominating the era of Hawai’i Statehood, thatching is considered primitive and replaceable.

Thatch Assembly with Rocks (2060s) attempts to fill a gap in the history of Hawai‘i architecture. The project yields an anachronism for contemplation. On one side, a history that could have been, where thatching is incorporated regionally into modern architecture surrounding Hawai‘i Statehood. On the other, a history possible a hundred years from now (2060s), at a time when the building code for indigenous structures has modified. In misplacing the assembly as an artifact in time, (II) the second strategy of material study emerges: the project is a material study. In the assembly, the primary material is Loulu, (pritchardia remota), a fan palm endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The materials, which used to be prevalent across all elevations is readily available and used historically for thatching. The fronds, which can remain dried on a tree for decades, are harvested only after dryness has subsumed its biological function to reach a final molecular outcome—in death the leaf secretes its own waterproofing. After harvest, the fronds are processed and organized for lashing. Conventionally, lashing is secured to a frame of similarly lashed wooden rods of varying circumferences. However, as a material study the palms are misplaced together with a sawn cut, hand notched timber frame. The pairing of thatch and sawn timber incorporates two disparate events in architecture to make new history. Rocks—the most sacred and contentious island-based materials— are placed in each module as an entrypoint for further discussion about the piece.

In this event of new history, (III) the third strategy reveals itself: the thatching is skewed in plan and reversed in section. This conceptual hint serves first to remind the participant this is not a house but a material study. As a material study, this creates various moments to focus conversation: (a) site, (b) intensification, (c) craft, (d) enclosure. Given its placement on site, (a) the orthogonal volume is skewed at 105.6 degrees (N to East) in reference to the position of the moon as it rises on the Spring Equinox. This angle is crossed with a second axis toward mauka-makai. The skewed operation of the rectangular volume enables the roof to separate from the walls resulting in the structure for thatching, which is then finally reversed. The reversal of thatching yields an affect of intensification. (b) Three exterior thatched planes turned inward intersect to simulate the appearance of a dense, perhaps urbanized condition; a courtyard, alleyway, or interstitial rooftop spaces. (c) The oblique geometry, as the participant moves around the assembly, appears to slip and elongate. Both faces of thatching become visible together at once. The frilly appearance of the typically outward facing thatch is revealed to be indeed profound—the rigor and craft of a thatch structure are best seen from its interior. The act of reversal interiorizes the exterior, and (d) the experience of the assembly begins to upend any notion of enclosure and place the question of indoor and outdoor within the actual material (and its land base). (IV) The final strategy is fleeting and experienced only during a short period of the day with the right weather. As the slope produces shade, the assembly demonstrates the thermal utility of the thatch. Compared to a roof made of copper, corrugated metal, or asphalt shingles, the thermal efficacy of loulu palm produces an environment that is several degrees cooler.

PROJECT TEAM

Curatorial Advisory: Margo Machida, Katherine Higgins, Greg Devork

Design: Sean Connelly (artist), Lopaka Aiwohi (hale builder), Avery Normandin, Ihilani Phillips, Iggy So

Project Manager: Yoko Ott

Installation Manager: Scott Lawrimore

Lead Install: Sean Connelly, Ihilani Phillips

Installation Assistants: AJ Feducia, Lia Fong, Spencer Agoston, Kurt Munchmeyer

Volunteers: Tim Connelly, Ikaika Ramones, Andi Charuk, Blake Miller, Marika Emi

Honolulu Biennial Foundation: Isabella Hughes, Katherine Tuider, Taiji Terasaki, Kristen Chan, Katherine Don, Sonny Ganaden, Shaunagh Guinness Robbins, Meli James, Gloria Lau, Heather Shimizu, Brett Zaccardi

Foster Botanical Garden: Joshyln Sand, Justin Rickard

KUA: Alex Connelly

Hui Ku Maoli Ola: Rick Barboza

University of Hawai‘i School of Architecture: Steve Hill

University of Hawai'i Department of Art and Art History: Jaimey Hamilton Farris

SELECTED PRESS:

Art Journal Open, CCA

Lei Magazine

Art Monthly Australasia